by Tzutzu Matzin

From Canyon Cinemazine #8: Cine-Espacios (2021-23). This interview was conducted on August 24, 2021. The Spanish-language version follows below.

If you find yourself in Mexico City wanting to stage a screening, filmmaker Elena Pardo is the person to talk to. She has the energy and network to connect you with the right folks at the ideal venue, and she knows the recipe for an ideal experimental film screening by heart.

In 2013 she co-founded the non-profit organization, Laboratorio Experimental de Cine (LEC), and has since been passionately involved in the Grupo de Cines Mutantes, advocating that “other cinemas” are included in public calls for production and exhibition financing.

Elena and I first met at the Primer Encuentro de Archivistas Audiovisuales de Oaxaca in 2014 and, ever since, have shared a mutual interest in cinema made on film across exhibition, preservation, and community training contexts. In this conversation we reflect on Elena’s work as a creator of cinematographic spaces–or, what she describes as, “making cinema happen in the interstices.”

Tzutzu Matzin (TZ): Elena, can you start by talking about the Laboratorio Experimental de Cine (LEC)?

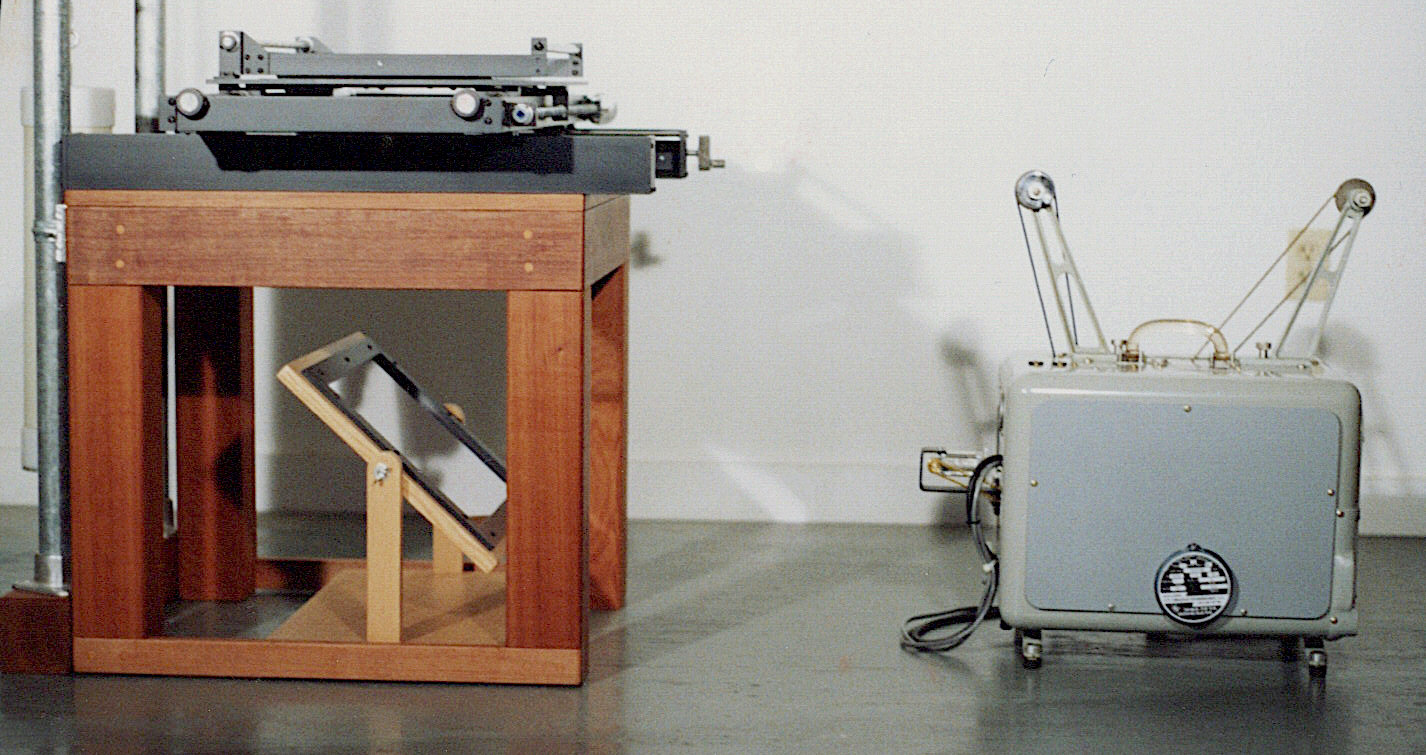

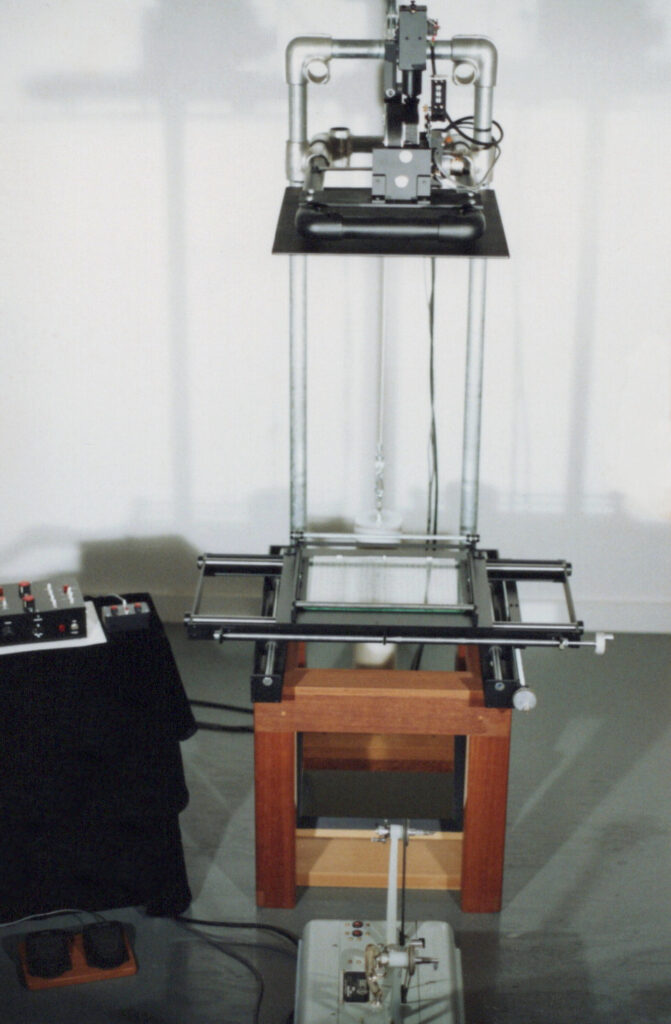

Elena Pardo (EP): Morris (Manuel Trujillo) and I staged cinema workshop trainings and experimental film screenings in many spaces for several years. We worked as collaborators in the expanded film collective, Trinchera Ensemble, performing at a variety of festivals around the world. Filmmakers we met on those trips along the way started to visit Mexico and we helped find them venues to perform at and share their work. One of the motivations for founding the LEC was to focus our energies on a single project, constructing a space in which we could nurture our experimental film community. Of course, we also knew that officially creating a non-profit organization would enable us to apply for grants and public funds that would professionalize a lot of what we had already been doing informally.

Starting LEC in 2013, we obtained our first formal gig through an exhibition program at the Centro de Cultura Digital (CCD) [Center for Digital Culture] organized by Mara Fortes and Garbiñe Ortega. This first commission to program expanded cinema was very lucky. There was a budget for each show, and we could invite both local and foreign artists. If artists were coming from abroad we would often collaborate with other festivals like Animasivo, El Nicho, or Ambulante to co-present events. That way we were able to bring Kerry Laitala, Guy Sherwin, Lyn Loo, and Takashi Makino to all do shows. Other times we took advantage of the fact that artists might already be passing through Mexico, and we staged an event around their travel schedule. This enabled us to see live shows by artists we admired, usually alongside a workshop where we were able to learn from them.

That was basically my start in film programming. I wrote to filmmakers requesting permission to see their films, and discovered that most of them were very accessible and wanted to show their work in Mexico. Back then it wasn’t so easy to stream short films online. We read about filmmakers in festival programs and cinema books, or from blogs and catalogs, but you couldn’t easily see their works. Now there is a lot more online, but for a long time this wasn’t the case. For us it was very important to be able to screen experimental cinema, ideally in its original format.

TZ: Are there specific theaters in Mexico City for screening experimental cinema on film?

EP: Surprisingly, there are not many institutional spaces that have their own film projectors anymore. Even some of those that did, like the IFAL [French Institute of Latin America], no longer do.

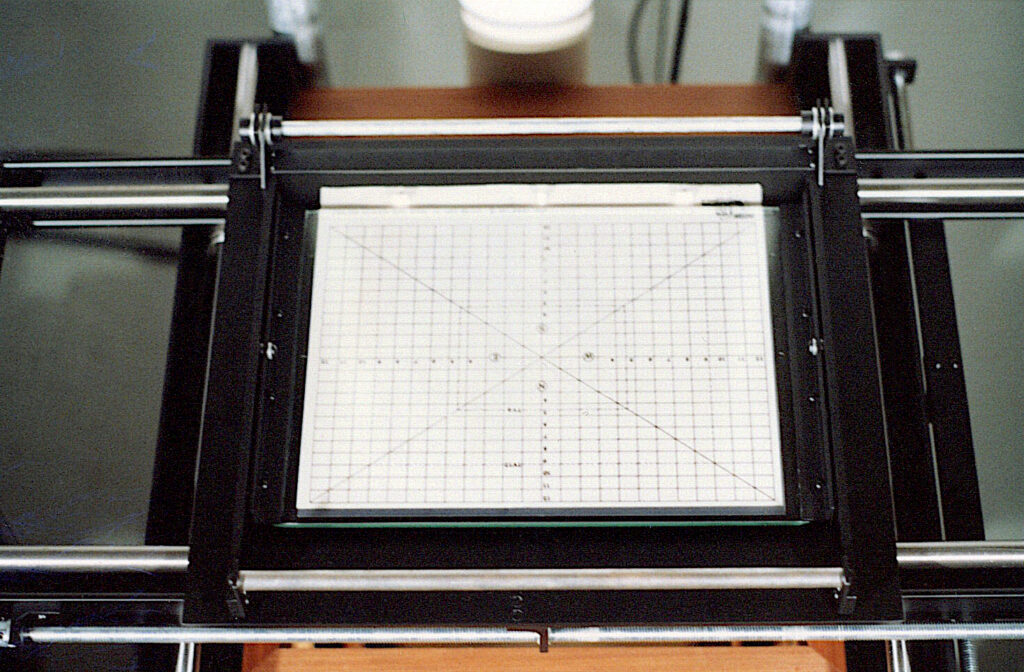

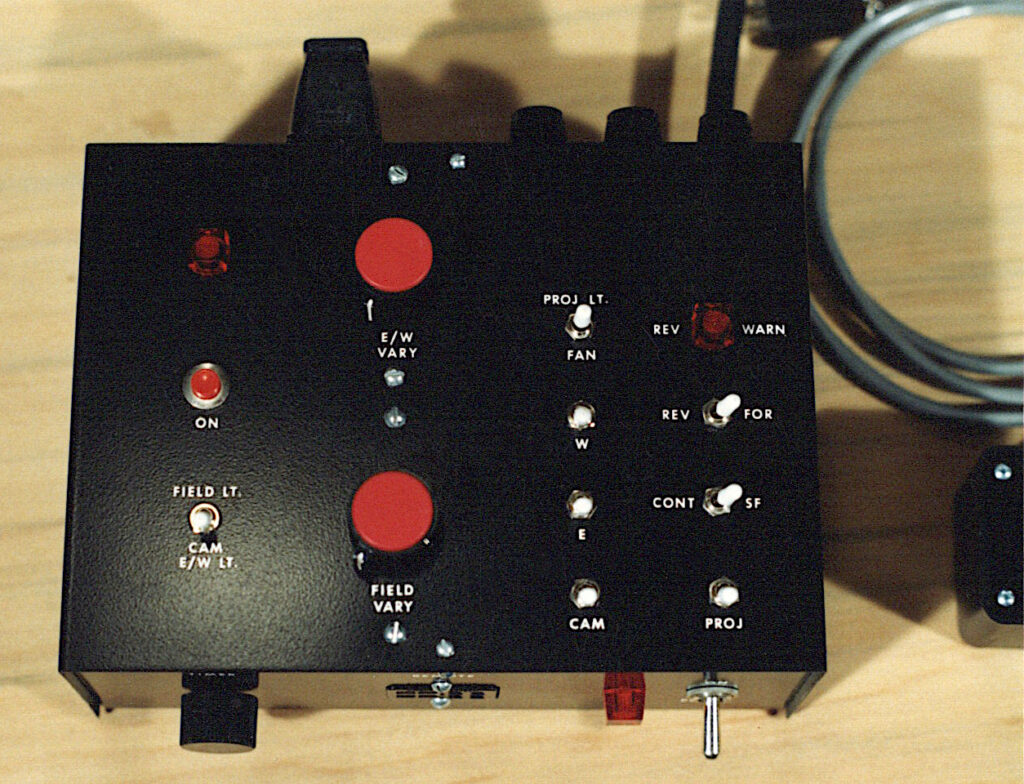

We’ve been helped by the fact that we have our own 16 mm projection gear–equipment that we’d amassed over the years and kept in good working order. That makes it easy for us to present work in most any space that opens its doors to us. On one occasion we projected in the auditorium of the Museo Tamayo, which is a very beautiful space. We did the same thing for the programs in the Centro de Cultura Digital’s multipurpose space (which is not really an auditorium, but rather a gallery space that can be adapted to meet the artist’s specifications). We managed to build a decent audience base that, over time, became a small community interested in taking workshops and eventually developing their own film projects.

In that period we also did a regular series at the Espectro Electromagnético that we called “CineClub 16.”

News spread to filmmakers in other countries that the LEC existed, and many of them reached out to us to arrange a screening while they were visiting Mexico City. That’s how we’ve met so many incredible filmmakers. We’ve even screened out-of-towners’ work who brought 16 mm prints along on their travels.

We’ve also collaborated with other exhibition projects, like the “15 asientos” [“15 seats”]: programmers who began programming screenings at IFAL with 16 mm projectors that they rented from us.

TZ: Tell me a little more about the history of some of your screenings.

EP: With the Espectro Electromagnético we would do a show once a month, more or less, looking for someone who wanted to show something specific. Or, if a filmmaker was passing through Mexico City they would tell us what they needed and we would bring the gear–usually a 16 mm projector.

Conversely, at the CCD almost everything we did was expanded cinema. For example, we programmed the work of Spanish filmmaker Luis Macías and they didn’t have a 16 mm projector (seeing as everything there is digital), but they were able to provide other things that complemented the presentation. Lastly, the LEC isn’t a cinema, per se. It doesn’t have a very large physical space [at its home studio in the Obrera neighborhood], but we have done two or three screenings there despite the fact that not many people fit. I think you’ve attended most all of those shows. Thus, our methodology for programming film shows is to collaborate with museums and other spaces.

Normally, we organize all logistics relating to the guest artists and equipment, but use the underexploited spaces of the host facility–like the auditorium in the Museo Tamayo. At the Tamayo during the Tacita Dean exhibition [November 2016 – March 2017], the museum invited us to do a three-month residency through its Education department with the goal of bringing the public closer to the work exhibited in the galleries. Programming 16 mm films was a core part of our activity there. By the end of the exhibition, we had garnered a bit of a following and many people turned out for the screenings; we showed works by Nathaniel Dorsky, Ben Russell, and Bill Brand, with each of them presenting their films in person.

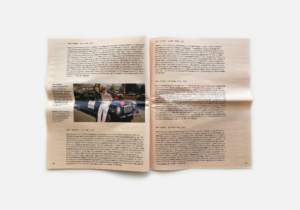

Along those lines we undertook a residency at Churubusco Studios from 2017-2018, which culminated with the international Independent Film Labs Meeting. Churubusco has several screening rooms with 16 mm and 35 mm projectors, which we took advantage of to screen works like La Fórmula Secreta [1965] by Rubén Gámez. One of the Film Labs Meeting attendees remarked to me: “You are very special because you are able to fill-in empty spaces, those ‘holes in the wall,’ carrying all you need with you.”

Many institutional venues don’t have regular programming because they lack ongoing funding for events. We have tried to capitalize on that absence. We arrive with all necessary ingredients in-tow: the projectors, the programming, and the public.

TZ: I also think that is a distinctive approach, in itself: looking for those interstitial spaces to make things happen. Has it always been like that?

EP: I think so. The Centro de Cultura Digital is a centralized place that doesn’t charge admission; they already had a built-in audience of curious minds, who eventually became an audience base for us. We always invite experimental sound artists to accompany expanded cinema works, and that universe has a loyal following of people that show up for things. We built a small following among those in the circle of musician Fernando Vigueras, who never missed a single show we did. At the CCD we even managed to attract audience demographics we’d never previously had: young people and art students. We never imagined those audiences for our programming, but as we’ve continued on they have followed us.

Then, other venues opened. Some of our most devout audience members decided to open their own venues–people like Annalisa D. Quagliata, who created La Cueva. El Espectro [Electromagnético] was another important venue. It was a disappointment when it closed [in 2018] because we did so many different kinds of shows there, 16 mm and expanded cinema. Lots of folks did their shows in that space. It was large, centrally located, and it became *the* place to meet up. Afterwards, the question was: ‘Where, now?’ That created something of a ‘scene,’ that I think is still present. Even though I have yet to go, I think of the Sala Gámez, which has since opened.

While they’re different kinds of projects, more spaces have opened up to satisfy audiences that want to see things. The LEC has never had the capacity to open its own screening venue, so we continue as squatters.

TZ: Can we backtrack and discuss the workshops that you staged with some of LEC’s invited artists?

EP: Sure. We were programming the work of filmmaker-heroes of ours, but thought that–in addition to, say, an expanded cinema performance–it would be cool for the local Mexico community to learn how these artists made their works. Like, we wondered: How does Alex MacKenzie create his Alex MacKenzie-thing? The workshops were a way of deepening the exhibition process for the works, but they also helped us financially subsidize the screenings with funding for pedagogical activities.

Soon, this grew a new arm of our audience: those interested in developing their own filmmaking practice. And, for those who weren’t experimental or expanded ‘makers’ it opened a new perspective on the featured artists: if you take the workshop, you’ll learn how the sausage gets made. You’ll get to see behind the magic curtain, kind of thing. This approach really paid off. Artist Nika Milano told me: “My own artist practice had its mind blown by the things I saw at CCD shows.” So, it’s an audience-augmentation strategy but also one that builds community. It brings together those who make, those who watch, and those who program. It’s an exponential kind of approach.

TZ: What are your thoughts about your new role as a film programmer, after working as a filmmaker for so long?

EP: The admin side of things requires so much time and effort that it can begin to drag on my filmmaker spirit. One is ever-aware of the energy required to ensure the event goes smoothly and that the guest artist has a good time: finding resources, planning the workshops, promoting the event, arranging lodging and transportation, serving as a nurse in medical situations, and even sometimes managing upset egos. There is a ton of invisible labor involved. Whenever we have monthly guests, that ends up being a lot of production. When we hosted Bill Brand for a workshop, he was already participating in another festival’s events and there were about ten different funding sources to coordinate.

I don’t know if I’ll ever reach the zenith of programming intensity that we had pre-pandemic [laughs], but all in all it was an incredible experience that taught me a lot. Perhaps, dividing the labor amongst more people would work better, but there just isn’t enough funding. Looking back, those well-funded early CCD years where it was just Morris and me, seem idyllic. We built a significant regular audience, but afterwards the funding source and dynamic changed. The community is still enthusiastic to help, but now the institutions are wary of cooperating with non-profit organizations and their piggy banks have run dry.

Of course, it is traditionally gauche to program one’s own work. Some do it, but for us it’s rare. Thus, spending effort organizing events can also cause my own art practice to suffer.

TZ: You also regularly programmed events at the Faro Aragón. While not as centrally located as the CCD, there were always a lot of interesting shows.

EP: Yes, we called that cycle of programs, “A Brief History of a Different Kind of Cinema.” I remember filmmaker Bruno Varela’s ‘tour,’ taking advantage of the funding we obtained to bring him here from Oaxaca. In the same day he led a workshop at LEC, followed by shows at the Faro and, then, Cineteca. In between we had lunch at the cantina El Recreo and I think he arrived to the latter half-tipsy. [Laughs]

The goal of that Faro Aragón series was to venture to less-traveled parts of the city and share experimental cinema. But we didn’t have the same amount of time to build an audience. It was far less gradual: “Let’s just do it!” It was in a gigantic auditorium, with seating for something like 3,000 people. People from the neighborhood often showed up; sometimes they liked it, sometimes they complained. We screened work that wasn’t what they expected to see in a cinema. Oftentimes building the audience is more work than simply running the projector. I think we only programmed one cycle, there, as LEC. Subsequent ones were done as ‘Reencuentros al Margen,’ or under other monikers. Eventually, I think people were into it but it can be hard to combat people’s fixed ideas of what cinema should be. That said, audiences can also be really eager for different kinds of cinema experiences. We found that happened working with young people in the state of Oaxaca.

TZ: Now that there are far more spaces, festivals, and venues to see experimental film in. Do you think building an audience is still as imperative?

EP: The landscape has changed a lot since we started. I think a lot more of the young people are hooked on experimental film. It’s definitely better. It is gratifying to have so many little venues and festivals interested in experimental film. Others are running shows now, and I can participate as an audience member or filmmaker and not as the Event Manager. There could be more expanded cinema kinds of things, but that always requires more gear, and more organization. Almost like a concert. There’s also still a lot of potential in sharing archival moving image material…the key is finding a way to make that fun. Like the series you, Lola, and I were doing–“Gin & Footage”–showing films informally in someone’s living room. [Laughs]

TZ: But the truth is: there’s always work involved in that.

EP: Yes, but it’s not work if you love doing it. It is never-ending, though: generating new programming ideas, equipment maintenance, finding funding, and preserving the possibility of screening work that we make and work that we want to see. Speaking of archives, I still want to be able to see films in their original 16 mm and 35 mm formats. It would be wonderful if we could find money to better equip venues for that.

Bit by bit we’ve made a lot of progress–finding interested audiences, willing institutional partners, and filmmakers who want to share. During the pandemic we created the Cines Mutantes group, which came about as a means to insert ourselves within the IMCINE [Mexico’s federal governmental body, which administers national film production, exhibition, and preservation funding] when we saw that the cinematographic laws were being rewritten and were open for public comment. Cines Mutantes has really helped us map the landscape of makers and venues across the country, and the results of those efforts show a lot of promise for the future.

Entrevista a Elena Pardo: Laboratorio Experimental de Cine

Tzutzu Matzin

24 de agosto 2021

Si estás en la Ciudad de México y quieres hacer una presentación, Elena Pardo es la cineasta ideal con quien debes hablar. Ella tiene la energía y la sensibilidad para conectar con las personas adecuadas, conoce el lugar perfecto para que todo pueda funcionar pues sabe cómo hacer que una proyección de cine experimental sea una gran experiencia, en un amplio sentido.

En el 2013 colaboró en la fundación del Laboratorio Experimental de Cine (LEC), asociación civil sin fines de lucro y, en los últimos años, se ha involucrado apasionadamente, a través del Grupo de Cines Mutantes, en una lucha para que los “otros cines” sean incluidos en las convocatorias públicas para financiamiento de producción y exhibición.

Elena y yo nos conocimos en el Primer Encuentro de Archivistas Audiovisuales de Oaxaca en el 2014, desde entonces nos ha unido un interés especial entre el cine hecho en formato fílmico, la exhibición, la preservación y la formación de públicos. En esta conversación reflexionamos en torno a su quehacer como creadora de espacios cinematográficos, o cómo ella dice “hacer que el cine ocupe espacios”.

Tzutzu Matzin (TZ): Elena, empecemos por hablar del Laboratorio Experimental de Cine (LEC).

Elena Pardo (EP): Morris (Manuel Trujillo) y yo, llevábamos muchos años dando talleres y programando cine experimental en distintos espacios. Para entonces, ya habíamos colaborado juntos en el colectivo de cine expandido Trinchera Ensamble con quienes habíamos asistido a varios festivales. Los cineastas que conocimos en esos viajes empezaron a venir a México y nosotros ayudábamos a encontrarles lugares para presentarse. Entonces, una de las razones para fundar el LEC fue concentrar nuestras energías en un proyecto propio e ir construyendo un espacio para nuestra comunidad de cine experimental. Por otro lado, pensamos que fundar una asociación civil, nos daría oportunidad de aplicar a fondos de financiamiento público que nos permitieran hacer actividades de manera profesional.

Abrimos el LEC en el 2013, en ese mismo año tuvimos la primera chamba formal, en el Centro de Cultura Digital (CCD), en un programa de exhibición organizado por Mara Fortes y Garbiñe Ortega. Esta primera comisión para programar cine expandido fue muy afortunada: teníamos un presupuesto para cada presentación y podíamos invitar a artistas locales y extranjeros. En el caso de los extranjeros a veces colaboramos con festivales, como Animasivo, El Nicho o Ambulante, para coproducir los eventos, así pudimos traer por ejemplo a Kerry Laitala, Guy Sherwin, Lyn Loo o Takashi Makino. En otros casos, aprovechamos a los artistas que venían pasando por México, para organizar la presentación en torno a sus viajes. Esto nos permitió ver en vivo a artistas que admiramos mucho, además, también casi en todos los casos se organizó un taller, con lo que pudimos aprender de todos ellos.

Así empecé a programar, me animé a escribir a cineastas, para pedir permiso de ver sus películas y me dí cuenta que la mayoría son muy accesibles, tenían ganas de mostrar su trabajo en México. Antes no era tan fácil ver cortos en línea, los conocíamos de programas de festivales o de libros, leías de ellos en catálogos o blogs, pero no podías ver las piezas. Ahora hay más cosas en línea, pero durante mucho tiempo no se pudo, por eso fue muy importante poder exhibir cine experimental, idealmente en su formato original.

TZ: ¿Hay en la Ciudad de México, salas específicas para el cine experimental en soporte fílmico?

EP: Sorprendentemente no hay muchos espacios institucionales que tengan sus propios proyectores, incluso salas que años atrás sí los tuvieron, como el IFAL (Instituto Francés de América Latina).

Nos ayudó tener nuestro propio equipo de proyección de 16mm, equipo que hemos juntado a lo largo de los años y que mantenemos en buen estado. Eso facilitó que pudiéramos presentar trabajos en cualquier espacio que nos abriera las puertas. En una época proyectamos en el auditorio del Museo Tamayo, que es hermoso. Lo mismo hicimos con los ciclos del Centro de Cultura Digital, en su Espacio Polivalente (que propiamente no es una sala, sino un lugar que se modifica de acuerdo a las necesidades de cada artista); logramos reunir a una buena audiencia que poco a poco se fue convirtiendo en una pequeña comunidad que tomaba los talleres, y algunos empezaron a raíz de eso a desarrollar proyectos propios

También, durante una época hicimos un ciclo en el Espectro Electromagnético, un programa que llamamos CineClub16.

Se corrió la voz, entre los cineastas de otros países, que existía este espacio, por lo que nos contactaban para organizarles su proyección cuando pasaban por la Ciudad de México. Así conocimos cineastas increíbles.

Hicimos algunas presentaciones de cineastas que traían sus materiales en 16mm.

También colaboramos con otros proyectos de exhibición, por ejemplo con los programadores de “15 asientos” quienes empezaron a programar con el IFAL y nosotros les rentábamos los proyectores.

TZ: Cuéntame un poco más, ¿cómo fueron estas proyecciones?

EP: Por ejemplo, con el Espectro Electromagnético nos juntábamos una vez al mes, más o menos, buscábamos si alguien quería mostrar algo, o si alguien andaba de paso por México, nos decían lo que necesitaban y nosotros llevábamos el equipo, usualmente en 16mm.

Por otro lado en el CCD, casi todo lo que hicimos era cine expandido, por ejemplo, programamos al cineasta español Luis Macías. Ahí por supuesto, no tenían un proyector de 16mm, porque todo es digital, pero tienen otras cosas que complementaban para hacer la presentación. Finalmente el LEC no es un cine, no tiene mucho espacio, hemos hecho dos o tres proyecciones (a las que seguro has ido), pero caben muy pocas personas. Entonces la manera de programar ha sido colaborar con (o “tomar”) museos y otros espacios.

Nosotros organizamos lo relacionado a los invitados y el equipo, pero usando los espacios que están ahí, lugares subutilizados, como, en esa época, el auditorio del Museo Tamayo. Llegamos ahí cuando fue la exposición de Tacita Dean y nos invitaron a hacer una residencia de tres meses en la Sala Educativa del Museo, con la intención de acercar al público a la obra expuesta en las salas. Parte de nuestras actividades era la programación de películas en 16mm. Al terminar la residencia ya habíamos generado un hábito en ese espacio, llegaba mucha gente a las proyecciones; ahí proyectamos trabajos de Nathaniel Dorsky, Ben Russell y Bill Brand, con ellos presentando sus películas.

Así también lo hicimos en los Estudios Churubusco entre el 2017 y 2018, cuando hicimos una residencia que culminó con el Encuentro de Laboratorios Fílmicos Independientes. En Churubusco tienen salas con proyectores 16mm y 35mm, que aprovechamos para compartir trabajos experimentales, como por ejemplo La Fórmula Secreta, de Rubén Gámez. Alguien que vino al encuentro nos dijo: “Ustedes son muy particulares porque ocupan lugares vacíos, o huecos. Ustedes llevan sus cosas”.

Hay muchos espacios institucionales que no tienen programación constante, porque no hay recursos económicos. Nosotros hemos intentado aprovechar ese vacío. Les llegamos con todo el kit: proyectores, programación y público.

TZ: Pienso que también es una cultura en sí, la cultura de buscar el huequito. ¿Crees que siempre ha sido así?

EP: Yo creo que sí. El Centro de Cultura Digital es un lugar céntrico y de acceso libre; ellos ya tenían personas que iban de curiosos, a ver que habían puesto, de esos curiosos se empezó a hacer un público. Invitamos siempre a músicos experimentales para acompañar la parte de cine expandido y la banda del sonido experimental es muy seguidora, si les gusta algo, empiezan a asistir. Se empezó a formar un grupo, del lado del músico Fernando Vigueras, que no se perdían ni una. Se juntó un público que no teníamos antes, gente joven, que estaba estudiando arte, llegaron grupos variados y personas que no imaginábamos que podían llegar. Conforme nos fuimos moviendo, nos iban siguiendo.

Y luego se empezaron a abrir otros lugares. Hay gente que iba a todo y que pensó que estaría bien abrir un cine, por ejemplo, yo creo que esa experiencia, animó en cierta medida a Annalisa D. Quagliata para crear La Cueva. El Espectro también era un lugar importante; cuando cerró, fue un bajón porque ahí hacíamos todo, hacíamos 16 mm y expandido. Ahí todo mundo hacía sus funciones, era grande, estaba céntrico y se convirtió en el lugar para reunirnos. De ahí se desprendió la necesidad de buscar, de preguntarnos “¿y ahora dónde?”. Yo creo que de ahí se fue generando una movidilla, que siento que sigue ahí, dando. Por ejemplo, actualmente se abrió la Sala Gámez, aunque aún no he ido.

Son esfuerzos muy distintos, pero al haber un público con ganas de ver cosas, se abren más espacios. Nosotros nunca hemos tenido la posibilidad o la capacidad de abrir un espacio de proyección, entonces seguimos siendo invasores eventuales.

TZ: ¿Podemos volver al tema de organizar talleres con los artistas que programas?

EP: Sí. Hasta ahora hemos programado el trabajo de cineastas que admiramos mucho y que han sido nuestra inspiración, pero pensamos que además de verlos durante una sesión de cine expandido, sería increíble para la comunidad local aprender cómo hacen su trabajo. Por ejemplo, nos preguntábamos ¿cómo hace Alex Mackenzie sus cosas? Entonces los talleres fueron una manera de profundizar en el proceso de producción de las piezas y además nos ayudó a subsidiar los eventos, porque con el presupuesto que pedíamos a las instituciones no era suficiente, pero con el taller podíamos completar lo que faltaba económicamente.

Creo que esto empezó a atraer a otro público, con interés de aprender y hacer crecer su propio trabajo. Y para quien no necesariamente quiere hacer cine experimental o expandido, les da otra perspectiva sobre esta práctica: si tomas un taller entiendes qué hay detrás, el trabajo que implica y por qué se hace, ya eres otro tipo de público si sabes “el truco”. Estas sesiones causaron su impacto, por ejemplo, la artista Nika Milano me dijo: “Las cosas que hacían en el CCD me volaron la cabeza para hacer mis propias cosas”. Entonces sí, es una forma de generar público y comunidad; hay quien hace, quien ve, quien programa y así no es que estás tú con tus tres amigos del principio, ya somos más.

TZ: ¿Qué piensas de haber pasado de ser realizadora a programar a otros artistas?

EP: Esto de la gestión requiere de mucho trabajo y tiempo, y te empieza a pesar como realizador, por la energía que le dedicas para que salga bien y para que la persona que invitas disfrute las actividades: buscar recursos, planear los talleres, hacer la promoción, que dónde se va a quedar, recogerlo del aeropuerto, que ya se enfermó, que ya se peleó. Implica muchas otras chambas paralelas, un montón de trabajo que nadie más va a hacer. Con sólo una vez al mes que alguien venía, ya era mucha producción, como Bill Brand, que daba un taller aquí, una actividad allá, participó en algún otro festival. Mínimo fueron diez actividades para financiar su estancia.

No sé si volvería a programar con tanta intensidad [risas], pero finalmente, creo que fue una buena experiencia porque aprendí muchas cosas. Tal vez haría este trabajo con más personas, repartir un poco, pero se necesitan más recursos que no hay. Los buenos tiempos fueron esos del CCD, donde tuvimos financiamiento y, a pesar de sólo estar Morris y yo, pronto se integraron más personas. Luego dejamos de tener los fondos y fue cambiando la situación. Ahora hay más personas dispuestas a ayudar, pero las instituciones parece que no quieren colaborar con las asociaciones civiles y no hay ni un peso.

Otra cosa que pasa es que no te vas a programar a ti mismo. Hay gente que sí lo hace, pero es raro que te incluyas como artista. Entonces tu trabajo empieza a sufrir por ese lado, no sabes cómo gestionar tu quehacer.

TZ: También hiciste lo del Faro Aragón, con un programa constante, pero la locación no era céntrica como en el CCD, fue una época en que había muchos eventos simultáneos.

EP: Sí, fue el ciclo que se llamó Una Breve Historia del Cine Diferente. Me acuerdo de la “gira” de Bruno Varela, aprovechando que vino a la Ciudad de México, le organizamos varias presentaciones: dio un taller en LEC, después fuimos primero al Faro, luego a Cineteca. Entremedias fuimos a comer a la cantina “El Recreo”, creo que llegamos medio borrachines [risas].

La intención de este ciclo fue ir hacia otras partes de la ciudad a mostrar cine experimental, pero no nos había dado tiempo de hacer un trabajo previo para encontrar al público interesado, como en el CCD. En el FARO fue en seco: “¡Ahí les vamos!”. Era un auditorio gigante, que había sido un cine para tres mil personas. Llegaban algunos vecinos, a veces les gustaba, a veces nos reclamaban. Llevábamos películas que, de entrada, no eran lo que esperaban ver. Hay que hacer muchísima más chamba a veces. Intentamos llevar cinéfilos ya convencidos desde otros puntos de la ciudad, organizábamos transportes para irnos juntos, no fue fácil. Hicimos un ciclo solamente como LEC. Después se dieron más talleres, llevamos otros proyectos como el de Reencuentros al Margen y otras personas y festivales programaron también cine experimental. Creo que con el tiempo sí fue surtiendo efecto la insistencia. A veces es difícil luchar contra las expectativas muy fijas de lo que se quiere ver. Hay otros casos en que encuentras un público con muchas ganas de ver cines diferentes, eso nos pasaba en Oaxaca o en los talleres que hacemos para jóvenes o niños.

TZ: Ahora hay más espacios para el cine experimental, hay festivales específicos o secciones para darle cabida a este tipo de obras. ¿Crees que hay que volver a trabajar sobre generar públicos?

EP: Ahora es diferente de cuando empezamos. Creo que mucha más gente joven está prendida con el tema del cine experimental. Sí, es un mejor momento. Es genial que haya tantas salitas y festivales que abran secciones o se dediquen exclusivamente al experimental, porque ya no se siente la necesidad apremiante de hacerlo una misma. Alguien más ya lo hace y ahora puedo participar como cineasta, ya no solamente como gestora. Quizás lo que aún no hay mucho, es exhibición de cine expandido. Ahí se requiere más equipo, más cosas, más producción, es casi como organizar un concierto. Por ahí podríamos seguir insistiendo. Y también hay un nicho en el tema del archivo, ahí hay mucho por hacer… porque la cosa es encontrar la manera de que se convierta en algo disfrutable. Como lo que hacemos con lo que llamamos Gin & Footage, eso que ideamos Lola, tú y yo para pasar películas sin formalidades… y gozar [risas].

TZ: Aunque la verdad siempre se convierte en trabajo.

EP: Sí, pero trabajo gozoso. Hay mucho por hacer, pero se necesita toda una vida: está el tema de la programación, de las máquinas que hacen falta para lo que queremos producir, la gestión de recursos, la preservación del cine que hacemos o que queremos ver. En el tema del archivo, me gustaría poder ver las películas en sus formatos originales, 35mm y 16mm. Estaría bien conseguir recursos para hacer copias nuevas y que algunas salas se equiparan.

Vamos poco a poco avanzando en los temas que nos gustan, encontrándonos con el público interesado y con otros gestores y realizadores. Todo ayuda: ya somos un montón haciendo esfuerzos de todos tipos. Durante la pandemia se gestó la movida de los Cines Mutantes, que nos organizamos para acercarnos al IMCINE cuando vimos que estaba reorganizándose la ley cinematográfica. Pero más allá de eso fue una manera de mapear a los cineastas y espacios afines por todo el país. Creo que de esa organización van saliendo resultados interesantes.